Year End Thoughts...

As the end of the year approaches, I sit and contemplate my 1st year experience with this, my first blog. I gotta say, writing these posts, giving vent to my thoughts and emotions regarding my hobby has been a highlight of the year past. This is fun, I get excited about writing posts and feel a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction when a thought comes together and gets posted. So I think I'll keep at it a bit longer.

I have written about several games this past year, and that was my original intent, the "Beyond" part of the title. White Box D&D retains a special place for me and hence the title. I have spoken to other gamers and many, like myself, are heavily influenced by the first game that introduces them to the hobby. There is certainly a bit of nostalgia at play, but the white box is much more to me. I really value using imagination and adding a personal element to each game. While many fantasy roleplaying games support this, the white box demands it. The chaos in those three little brown books requires the player/referee to impose some degree of order, adding to elements which are incomplete or creating from whole cloth those that are totally missing.

The White Box, by design or blunder, gives a good fun game...most of the time. It is more referee dependent than many games and suffers when run by a poor referee, but what game isn't better with a competent, or better yet, inspired referee! Using the rules pretty-much as written, the so-called Vancian magic system makes magic manageable without being too overpowered. Combat results have a random element that keeps things lively, but it's tempered with predictability. After a couple rounds one can generally see where the combat outcome is heading giving the players a chance to scoot out, or maybe expend a limited resource high-level spell to change the momentum. And combat is fast paced, something I have come to prefer over super crunchy "realistic" systems. The AC and hit point systems allow the character to get tougher as they level up and acquire treasures, thus giving them the ability to take on even greater challenges.

As with any system, environment/milieu or game setting can greatly effect the overall fun level. It is at this milieu or setting level that the referee really creates the game in many ways. The rules are how you play, but the setting is what you play. Some settings are better at creating an environment for adventure than others and it's not always the most well developed settings that do this. More to the point, I would say a setting, or milieu, needs to be well realized. The setting or milieu is much like the stage where players will act and the story will unfold. The referee needs to have given thought to how the setting handles a number of game requirements. On this matter I have a few thoughts I phrase as questions for the referee.

Regarding background history, does it help players create interesting PCs? Does the history affect the present in any meaningful way? How common is common knowledge? These are the kinds of queries a referee might use to help realize their setting. Who have been the actors on the world stage of the past? Were they PC types? Gods? Are there any adventure hooks that dangle from your world history?

Another referee query might be do you want the campaign to be epic in nature or personal? Are the adventure hooks consistent with that goal? What about patrons? Have you given any thought to who the PCs might work for? Are the NPCs mostly commoners or kings and queens? Is there a preset villain or do the PCs make their enemies along the way? How do you want to reward your PCs? What will be their motivation, wealth, fame, honor and glory, power? The rewards can shape PC motivation and how the players measure their success.

Magic and magic items are another area where the referee can greatly shape the environment of the game. What role does magic play in the setting? Does it act like technology, is it rare and feared? Is it tightly controlled? Does magic corrupt those who use it? How do PCs acquire magic items? Are there common items or are all magic items unique with their own history? Are magic items available for sale or manufacture?

Some game systems come out of the box tightly linked to a specific setting, others not so much. White box has a bit of a default setting in the choice the designers make of classes, monsters, experience and alignment system, but it is also easily modified without breaking anything. For me this is a strong point in favor of the rules. I very much enjoy tinkering with my RPG as a creative outlet. As the year wraps up, I find myself back at the beginning, singing the praises of the White Box. It really has been a life altering experience for me.

Being the observations, recollections and occasional ramblings of a long-time tabletop gamer.

Wednesday, December 30, 2015

Tuesday, December 22, 2015

High Fantasy

"Imagination is the heart and soul of High Fantasy"

With those words author Jeffrey C. Dillow begins his Introduction to High Fantasy (HF). Published in 1978, HF is one of the first generation reaction games, a reaction to white box in that the author likes the idea of using one's imagination in fantasy roleplaying, but thinks the rules can be improved, in part by being more realistic. Mr. Dillow follows the lead of many of the fantasy game designers of the period by referencing the literature of R.E. Howard and J.R.R. Tolkien as direct influences. Mr. Dillow states the rules allow players to experience adventure similar to that found in the works of their favorite authors through the actions of their player characters. I must admit being able to act out such adventures through a character in such a game appealed to me from the beginning (and obviously still does).

HF is a percentile system and has the logical transparency one usually associates with such systems. People generally understand that there is a percentage chance of certain things happening and that skill and circumstances can alter that percentage. As long as a game presents logical percentages, it can seem very realistic just by this transparency. HF offers the player a choice of four basic character classes, warrior, wizard, animal master and alchemist. There are also subclasses which allow the PC to specialize in certain skill sets. Each PC has an offensive total affected by scores in strength and coordination and a defensive total affected by the score in coordination. Quickness determines who goes first and is affected by weapon speed. Combat is a matter of subtracting the target's defensive total from the attacker's offensive total and rolling percentile dice. Consulting a table gives the outcome and any damage taken by the target reduces armor value and defensive and offensive totals.

A beginning spell caster may know 1 or more magic spells which are held in a special book. The spell book in HF is unique (to my knowledge) in roleplaying. It is a sentient thing which the wizard must attune/imprint to in order to use. The book assists the wizard in casting spells, is immune to most forms of damage, but can die. If killed, the book's cover fades and loses it's peculiar character (face or whatever), the pages fall out and the wizard is wise to soon seek a replacement. Many spells can be memorized allowing the caster to quickly throw the spell without the aid of the spell book, others are not able to be memorized and must be cast directly from the book. Spells cost mana points (lowering the wizard's daily supply of such points) which shapes the aether (from the environment) which powers the spell. This is an interesting theory of magic which allows for the traditional limited spell points/mana and environmental effects such as aether rich/poor areas. Many spells have multiple planes or power levels and can be cast with increasing effect at the higher planes. The rules for familiars include some unusual creatures, such as a ball of light or a human, and familiars can themselves cast spells.

HF includes many of the usual fantasy monsters with a few blatant name alterations in the case of IPs such as the Ehnt and the Balro. HF is a humanocentric game in general, but there is an option in the back of the book to allow Tolkien-style Hobbits, Dwarves and Elves to be played as PCs if desired/allowed. A short essay on developing a game world is included near the end for Judges, as the HF referee is referred to. In it is advice on designing the dungeon or temple for a first adventure, gradually adding to the world as the PCs continue to explore. Advice is given on economics, treasure and monster challenges with a goal of keeping the campaign balanced and playable. As they acquire wealth there are suggestions for the PCs spending it based on class, such as building a laboratory for an alchemist, a library and workshop for a wizard, etc.

The HF story is an adventure itself. According to gamer legend, the original 48 page booklet was self published by Mr. Dillow from the game he and friends played while in college. HF sold well enough to come to the attention of a major publisher (Reston) who produced an expanded 196 page edition and several additional adventure volumes which are well regarded in the hobby. This publisher was able to put a hardcover HF on the shelves of retail bookstores as well as hobby shops and for a while (early 80's) the hobbyist could visit most bookstore chains and find a selection of hardcover roleplaying books including AD&D, RuneQuest, DragonQuest and High Fantasy. In many ways it was a Golden Age for the hobby. Then this all changed and HF (along with several other hardcover RPGs) and Mr. Dillow himself disappeared from the hobby. He has recently returned, however, with the publication of a new HF novel titled When Magics Meet.

High Fantasy is a game I first acquired in the early 1980's. I have read it often and find I like many of the ideas presented therein. I have only played it solo and can recommend the solo adventures as being some of the best I have encountered. They are well written, meaty and have good replayability. The artwork in the early, self published (Fantasy Productions, Inc.) edition is in my opinion superior to the later (Reston Publishing Company, Inc.) edition. The larger size of the early edition also makes the combat table easier to read. With Mr. Dillow's return to the hobby and the current interest in old school games, might I hope for a new edition/reprint of High Fantasy? Maybe then I could find a group interested in a friendly game of High Fantasy!

With those words author Jeffrey C. Dillow begins his Introduction to High Fantasy (HF). Published in 1978, HF is one of the first generation reaction games, a reaction to white box in that the author likes the idea of using one's imagination in fantasy roleplaying, but thinks the rules can be improved, in part by being more realistic. Mr. Dillow follows the lead of many of the fantasy game designers of the period by referencing the literature of R.E. Howard and J.R.R. Tolkien as direct influences. Mr. Dillow states the rules allow players to experience adventure similar to that found in the works of their favorite authors through the actions of their player characters. I must admit being able to act out such adventures through a character in such a game appealed to me from the beginning (and obviously still does).

HF is a percentile system and has the logical transparency one usually associates with such systems. People generally understand that there is a percentage chance of certain things happening and that skill and circumstances can alter that percentage. As long as a game presents logical percentages, it can seem very realistic just by this transparency. HF offers the player a choice of four basic character classes, warrior, wizard, animal master and alchemist. There are also subclasses which allow the PC to specialize in certain skill sets. Each PC has an offensive total affected by scores in strength and coordination and a defensive total affected by the score in coordination. Quickness determines who goes first and is affected by weapon speed. Combat is a matter of subtracting the target's defensive total from the attacker's offensive total and rolling percentile dice. Consulting a table gives the outcome and any damage taken by the target reduces armor value and defensive and offensive totals.

A beginning spell caster may know 1 or more magic spells which are held in a special book. The spell book in HF is unique (to my knowledge) in roleplaying. It is a sentient thing which the wizard must attune/imprint to in order to use. The book assists the wizard in casting spells, is immune to most forms of damage, but can die. If killed, the book's cover fades and loses it's peculiar character (face or whatever), the pages fall out and the wizard is wise to soon seek a replacement. Many spells can be memorized allowing the caster to quickly throw the spell without the aid of the spell book, others are not able to be memorized and must be cast directly from the book. Spells cost mana points (lowering the wizard's daily supply of such points) which shapes the aether (from the environment) which powers the spell. This is an interesting theory of magic which allows for the traditional limited spell points/mana and environmental effects such as aether rich/poor areas. Many spells have multiple planes or power levels and can be cast with increasing effect at the higher planes. The rules for familiars include some unusual creatures, such as a ball of light or a human, and familiars can themselves cast spells.

HF includes many of the usual fantasy monsters with a few blatant name alterations in the case of IPs such as the Ehnt and the Balro. HF is a humanocentric game in general, but there is an option in the back of the book to allow Tolkien-style Hobbits, Dwarves and Elves to be played as PCs if desired/allowed. A short essay on developing a game world is included near the end for Judges, as the HF referee is referred to. In it is advice on designing the dungeon or temple for a first adventure, gradually adding to the world as the PCs continue to explore. Advice is given on economics, treasure and monster challenges with a goal of keeping the campaign balanced and playable. As they acquire wealth there are suggestions for the PCs spending it based on class, such as building a laboratory for an alchemist, a library and workshop for a wizard, etc.

The HF story is an adventure itself. According to gamer legend, the original 48 page booklet was self published by Mr. Dillow from the game he and friends played while in college. HF sold well enough to come to the attention of a major publisher (Reston) who produced an expanded 196 page edition and several additional adventure volumes which are well regarded in the hobby. This publisher was able to put a hardcover HF on the shelves of retail bookstores as well as hobby shops and for a while (early 80's) the hobbyist could visit most bookstore chains and find a selection of hardcover roleplaying books including AD&D, RuneQuest, DragonQuest and High Fantasy. In many ways it was a Golden Age for the hobby. Then this all changed and HF (along with several other hardcover RPGs) and Mr. Dillow himself disappeared from the hobby. He has recently returned, however, with the publication of a new HF novel titled When Magics Meet.

High Fantasy is a game I first acquired in the early 1980's. I have read it often and find I like many of the ideas presented therein. I have only played it solo and can recommend the solo adventures as being some of the best I have encountered. They are well written, meaty and have good replayability. The artwork in the early, self published (Fantasy Productions, Inc.) edition is in my opinion superior to the later (Reston Publishing Company, Inc.) edition. The larger size of the early edition also makes the combat table easier to read. With Mr. Dillow's return to the hobby and the current interest in old school games, might I hope for a new edition/reprint of High Fantasy? Maybe then I could find a group interested in a friendly game of High Fantasy!

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

Beasts, Men & Gods

Plausibility in Roleplaying

Beasts, Men & Gods (BMG)was first published in 1980 and recently received a rebirth as the revised second edition. In the About this "Revised Second Edition" BMG, author Bill Underwood tells us that he wrote BMG while a college student 1977-1980. In his Introduction Mr. Underwood explains his desire to improve reality or "plausibility", as he refers to it, in his fantasy game. Mr. Underwood specifically mentions hit points and magic as two areas where realism seems lacking in other games. These are two areas where BMG differs from white box and I think Mr. Underwood offers interesting alternatives.

BMG assigns about 7 hit points to each character. This may vary slightly, but not by more than a digit or so. The character also gets at least 1 stamina point, which increases as they level-up. Damage is taken from stamina until that is gone and then deducted from hit points. Hit points represent flesh and blood, stamina is luck, sixth sense, dodging, etc. A critical hit bypasses stamina and damage is taken directly on hit points. Stamina is easily recovered with a few minutes rest and/or a drink of water. Hit points, representing real wounds is slower to heal.

Magic in BMG makes use of Mana points and also costs stamina to cast. There are 10 areas or schools of magic and three types of priestly magic. Casting magic above one's mastery level can result in mishap. BMG makes use of character classes and levels and dwarves and elves are each a class. Saving throws are used, although the list includes bleeding, shock, stress and unconsciousness as well as the more traditional poison and magic saves. Combat is percentile based and includes both melee and spiritual combat mechanics. The bestiary section includes the usual monsters.

Mr. Underwood stresses, like many authors of his day, that the rules as written are suggestions and he invites the player/referee to alter the rules to meet their expectations. He suggests the reader draw from other sources, especially fantasy and sword & sorcery literature for rule and setting inspiration. I would add that drawing from various rules and other systems is also good practice.

Although BMG is an older game in the spirit of those first generation published houserules or "improvements on white box" it is a recent discovery for me and I am glad it is available again. I like the idea of separating the hit point pool into something like stamina and body points. The combat and magic systems are certainly more complex than white box and with more study I may agree with Mr. Underwood that they improve on "plausibility". However at this point in my gaming career, I am rather content with a game being just a game as long as it's fun.

Beasts, Men & Gods (BMG)was first published in 1980 and recently received a rebirth as the revised second edition. In the About this "Revised Second Edition" BMG, author Bill Underwood tells us that he wrote BMG while a college student 1977-1980. In his Introduction Mr. Underwood explains his desire to improve reality or "plausibility", as he refers to it, in his fantasy game. Mr. Underwood specifically mentions hit points and magic as two areas where realism seems lacking in other games. These are two areas where BMG differs from white box and I think Mr. Underwood offers interesting alternatives.

BMG assigns about 7 hit points to each character. This may vary slightly, but not by more than a digit or so. The character also gets at least 1 stamina point, which increases as they level-up. Damage is taken from stamina until that is gone and then deducted from hit points. Hit points represent flesh and blood, stamina is luck, sixth sense, dodging, etc. A critical hit bypasses stamina and damage is taken directly on hit points. Stamina is easily recovered with a few minutes rest and/or a drink of water. Hit points, representing real wounds is slower to heal.

Magic in BMG makes use of Mana points and also costs stamina to cast. There are 10 areas or schools of magic and three types of priestly magic. Casting magic above one's mastery level can result in mishap. BMG makes use of character classes and levels and dwarves and elves are each a class. Saving throws are used, although the list includes bleeding, shock, stress and unconsciousness as well as the more traditional poison and magic saves. Combat is percentile based and includes both melee and spiritual combat mechanics. The bestiary section includes the usual monsters.

Mr. Underwood stresses, like many authors of his day, that the rules as written are suggestions and he invites the player/referee to alter the rules to meet their expectations. He suggests the reader draw from other sources, especially fantasy and sword & sorcery literature for rule and setting inspiration. I would add that drawing from various rules and other systems is also good practice.

Although BMG is an older game in the spirit of those first generation published houserules or "improvements on white box" it is a recent discovery for me and I am glad it is available again. I like the idea of separating the hit point pool into something like stamina and body points. The combat and magic systems are certainly more complex than white box and with more study I may agree with Mr. Underwood that they improve on "plausibility". However at this point in my gaming career, I am rather content with a game being just a game as long as it's fun.

Thursday, December 10, 2015

Roleplay & Adventure

Game Style

The white box has it's roots in wargaming and says so, Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns... So we can look at white box and the hobby it has inspired as a wargame...Playable with Paper and Pencil and Miniature Figures and many of us continue to play it exactly that way. Some rule systems are more tied to the use of miniatures than others and some systems encourage "theater of the mind" play where all the action takes place in the imagination of the players. Regardless of whether miniature figures are used or not, players quickly start to identify with their game tokens, called player characters or PCs, and start adding elements of personality, either their own or that of a make-believe character like out of a book or play, etc. We now call this roleplaying.

Some rule systems and some play groups put more emphasis on roleplay than others. For some campaigns the roleplay is central and the PC is assigned, either by choice or random chance, various personality traits and personal history and the player roleplays the created PC as if he/she had an actual life complete with beliefs, values, goals, quirks, relationships...pretty much everything that makes up a person and a life. In such a campaign, what the PC does in between adventures is just as important as anything that happens in a dungeon (or anywhere else). The referee and players in such a game often use distinct voices for the PCs and NPCs and try to think like the character would think. Playing the game "in character" can be a major goal and much of the satisfaction of such games is in following a character's life story as it develops.

One of the appeals of the white box and systems that follow is flexibility. The game can be played in many different ways/styles, with emphasis sometimes placed on one aspect or another. For some campaigns the PC remains a game piece, a token or means for the player to participate in the action. Such games place adventure above roleplay and sometimes refer to the game as adventure gaming rather than roleplaying. The adventure game may be played more as a series of stand-alone game sessions where no one is really concerned with what the imaginary PCs do in between game sessions. They have no "life" outside the dungeon. The white box emphasis on dungeon and wilderness encounters supports this manner of play and many campaigns have really been little more than a series of self-contained adventures making use of a common cast of PCs who level-up between adventures.

The adventure game style of play emphasizes aspects of the rule system with more focus on exploration of a prepared environment, dungeon, wilderness or urban setting, etc. Rules mastery and the use of tactics are valued player skills and characters are often designed with their tactical role in the party make-up in mind. Overcoming challenges and making discoveries provide the players with satisfaction as well as advancing their PC.

Rules realism is approached differently depending on whether the emphasis is on roleplay or adventure. The desire for verisimilitude seems to frequently lead players into a search for realism in the game. For the roleplayer this often takes the form of more detailed character generation rules and stricter rules on how the character is played and how character advancement is handled. For the adventurer realism is often reflected in detailed combat and magic rules that allow for the use of tactics and teamwork.

My early experience with white box began much like the adventure game extreme with each player controlling a number of PCs, several usually "dying" during the game session. As the years roll by the groups I game with have become more interested in the PCs as "people" and have started to do more and more roleplaying. The adventure part remains very important in that we like challenges and exploration and appreciate good game play. Attendance at conventions has allowed me to play a number of systems with various referees and players and both roleplay and adventure style games seem popular and easily found. Among the groups that I regularly game with our sessions are a mixture of the two, adventure games with roleplaying. Some players emphasize one style over the other, but the referee and game mechanics generally support both.

The white box has it's roots in wargaming and says so, Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns... So we can look at white box and the hobby it has inspired as a wargame...Playable with Paper and Pencil and Miniature Figures and many of us continue to play it exactly that way. Some rule systems are more tied to the use of miniatures than others and some systems encourage "theater of the mind" play where all the action takes place in the imagination of the players. Regardless of whether miniature figures are used or not, players quickly start to identify with their game tokens, called player characters or PCs, and start adding elements of personality, either their own or that of a make-believe character like out of a book or play, etc. We now call this roleplaying.

Some rule systems and some play groups put more emphasis on roleplay than others. For some campaigns the roleplay is central and the PC is assigned, either by choice or random chance, various personality traits and personal history and the player roleplays the created PC as if he/she had an actual life complete with beliefs, values, goals, quirks, relationships...pretty much everything that makes up a person and a life. In such a campaign, what the PC does in between adventures is just as important as anything that happens in a dungeon (or anywhere else). The referee and players in such a game often use distinct voices for the PCs and NPCs and try to think like the character would think. Playing the game "in character" can be a major goal and much of the satisfaction of such games is in following a character's life story as it develops.

One of the appeals of the white box and systems that follow is flexibility. The game can be played in many different ways/styles, with emphasis sometimes placed on one aspect or another. For some campaigns the PC remains a game piece, a token or means for the player to participate in the action. Such games place adventure above roleplay and sometimes refer to the game as adventure gaming rather than roleplaying. The adventure game may be played more as a series of stand-alone game sessions where no one is really concerned with what the imaginary PCs do in between game sessions. They have no "life" outside the dungeon. The white box emphasis on dungeon and wilderness encounters supports this manner of play and many campaigns have really been little more than a series of self-contained adventures making use of a common cast of PCs who level-up between adventures.

The adventure game style of play emphasizes aspects of the rule system with more focus on exploration of a prepared environment, dungeon, wilderness or urban setting, etc. Rules mastery and the use of tactics are valued player skills and characters are often designed with their tactical role in the party make-up in mind. Overcoming challenges and making discoveries provide the players with satisfaction as well as advancing their PC.

Rules realism is approached differently depending on whether the emphasis is on roleplay or adventure. The desire for verisimilitude seems to frequently lead players into a search for realism in the game. For the roleplayer this often takes the form of more detailed character generation rules and stricter rules on how the character is played and how character advancement is handled. For the adventurer realism is often reflected in detailed combat and magic rules that allow for the use of tactics and teamwork.

My early experience with white box began much like the adventure game extreme with each player controlling a number of PCs, several usually "dying" during the game session. As the years roll by the groups I game with have become more interested in the PCs as "people" and have started to do more and more roleplaying. The adventure part remains very important in that we like challenges and exploration and appreciate good game play. Attendance at conventions has allowed me to play a number of systems with various referees and players and both roleplay and adventure style games seem popular and easily found. Among the groups that I regularly game with our sessions are a mixture of the two, adventure games with roleplaying. Some players emphasize one style over the other, but the referee and game mechanics generally support both.

Tuesday, December 8, 2015

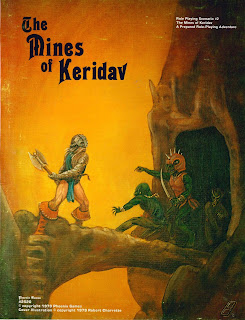

The Mines of Keridav

Generic Play-aid

Over the weekend a friend gave me some old roleplaying publications including The Mines of Keridav by Kerry Lloyd. The Mines has a copyright of 1979 and is published by Phoenix Games, the same company that published Dana Lombardy's Streets of Stalingrad monster wargame. (Streets of Stalingrad is one of the classic map and counter wargames and a personal favorite, but I was unaware Phoenix Games published RPG play-aids too.) The play-aid says it can be used with any system and lists Arduin Grimoire, Chivalry & Sorcery, Dungeons & Dragons, Runequest and Tunnels & Trolls as possible rules. The list covers what might be considered the "Big" games circa 1979.

The play-aid is 24 pages including 5 color maps on heavy stock and several b&w small area maps. In addition to the mines themselves, an entire valley is mapped and described. There is enough here for a small sandbox type campaign, a number of villages, bandits and other threats to hunt down and deal with, taverns full of rumors, gambling and excitement and several notable NPCs with whom to interact and develop side plots with. There's even a princess to save and a keep to win control of. The Mines was written to be combined with another play-aid by Mr. Lloyd titled the Demon Pits of Caeldo (hinted at in The Mines). The Demon Pits was supposed to follow the publication of The Mines of Keridav under the Phoenix Games label, but Phoenix Games went out of business before that happened. Fortunately Mr. Lloyd was able to publish Demon Pits of Caeldo under Gamelords, a company he co-founded in 1980 to publish Thieves Guild products. Together The Mines and Demon Pits might just make a pretty nice campaign.

Over the weekend a friend gave me some old roleplaying publications including The Mines of Keridav by Kerry Lloyd. The Mines has a copyright of 1979 and is published by Phoenix Games, the same company that published Dana Lombardy's Streets of Stalingrad monster wargame. (Streets of Stalingrad is one of the classic map and counter wargames and a personal favorite, but I was unaware Phoenix Games published RPG play-aids too.) The play-aid says it can be used with any system and lists Arduin Grimoire, Chivalry & Sorcery, Dungeons & Dragons, Runequest and Tunnels & Trolls as possible rules. The list covers what might be considered the "Big" games circa 1979.

The play-aid is 24 pages including 5 color maps on heavy stock and several b&w small area maps. In addition to the mines themselves, an entire valley is mapped and described. There is enough here for a small sandbox type campaign, a number of villages, bandits and other threats to hunt down and deal with, taverns full of rumors, gambling and excitement and several notable NPCs with whom to interact and develop side plots with. There's even a princess to save and a keep to win control of. The Mines was written to be combined with another play-aid by Mr. Lloyd titled the Demon Pits of Caeldo (hinted at in The Mines). The Demon Pits was supposed to follow the publication of The Mines of Keridav under the Phoenix Games label, but Phoenix Games went out of business before that happened. Fortunately Mr. Lloyd was able to publish Demon Pits of Caeldo under Gamelords, a company he co-founded in 1980 to publish Thieves Guild products. Together The Mines and Demon Pits might just make a pretty nice campaign.

Friday, December 4, 2015

A Place of Mystery and Treasure

Read Only Game

In Chivalry and Sorcery, authors Ed Simbalist and Wilf Backhaus write about a place of mystery or treasure as opposed to the dungeon found in other games (meaning white box, etc.). The difference is one of design philosophy as well as scale. The place of mystery or treasure can be anything, as can a dungeon, really. A tower, ruin, or other above ground structure, a mine, cavern, tomb or other underground complex, or a forest, island, or other place can serve as the location for adventure. The suspected presence of treasure may be the motivation to visit such place or there may be other "hooks" such as rescuing the princess from the tower.

What Mr. Simbalist and Mr. Backhaus seem to be arguing against in C&S is the megadungeon referenced in white box as simply "the dungeon" and which forms the centerpiece of many old school campaigns. The megadungeon concept is based on the campaign consisting of numerous trips into the multilevel dungeon to defeat monsters and traps and acquire treasure. The dungeon is designed by the referee with levels on which are found increasingly difficult challenges and correspondingly increased rewards in the form of treasure. The rationale for such dungeon is often a crazy old arch-mage who built it and stocked it with critters, traps and treasure, for some generally unknown reason. Such dungeons have been labeled "fun-parks" when each room basically presents a new challenge, often with a corresponding reward and the adventuring party moves from room-to-room much like a "fun park" patron moves from booth to booth overcoming the challenge at each and earning the reward. Often little thought is given to the relationship of any occupants of one room to another.

In C&S the authors state that the location of monsters, traps, and treasures should be logical and justified. Here we see the concept of realism applied to the design of the dungeon or other place of mystery. Thought should be given to how the dungeon operates as an environment for those resident monsters as well as the occasional adventuring PC. C&S advocates the campaign including several adventure sites rather than a single large dungeon. The places of mystery or treasure are each smaller than a megadungeon and may be completely explored in only a session of so of play. They are presumably part of some adventure storyline which gives the PCs reason to visit them and ties them into the greater milieu or Grand Campaign.

The creators of C&S state their goal of creating a game where the dungeon and wilderness adventure are only part of the game experience. Adventure can also be found in social interaction, feudal tournaments, formal warfare, politics and economics and C&S encourages players to explore these areas as well as in the places of mystery and treasure. I have never gamed C&S as a system, but many of the ideas found in this 1977 publication influence the way I play all other roleplaying and adventure games.

In Chivalry and Sorcery, authors Ed Simbalist and Wilf Backhaus write about a place of mystery or treasure as opposed to the dungeon found in other games (meaning white box, etc.). The difference is one of design philosophy as well as scale. The place of mystery or treasure can be anything, as can a dungeon, really. A tower, ruin, or other above ground structure, a mine, cavern, tomb or other underground complex, or a forest, island, or other place can serve as the location for adventure. The suspected presence of treasure may be the motivation to visit such place or there may be other "hooks" such as rescuing the princess from the tower.

What Mr. Simbalist and Mr. Backhaus seem to be arguing against in C&S is the megadungeon referenced in white box as simply "the dungeon" and which forms the centerpiece of many old school campaigns. The megadungeon concept is based on the campaign consisting of numerous trips into the multilevel dungeon to defeat monsters and traps and acquire treasure. The dungeon is designed by the referee with levels on which are found increasingly difficult challenges and correspondingly increased rewards in the form of treasure. The rationale for such dungeon is often a crazy old arch-mage who built it and stocked it with critters, traps and treasure, for some generally unknown reason. Such dungeons have been labeled "fun-parks" when each room basically presents a new challenge, often with a corresponding reward and the adventuring party moves from room-to-room much like a "fun park" patron moves from booth to booth overcoming the challenge at each and earning the reward. Often little thought is given to the relationship of any occupants of one room to another.

In C&S the authors state that the location of monsters, traps, and treasures should be logical and justified. Here we see the concept of realism applied to the design of the dungeon or other place of mystery. Thought should be given to how the dungeon operates as an environment for those resident monsters as well as the occasional adventuring PC. C&S advocates the campaign including several adventure sites rather than a single large dungeon. The places of mystery or treasure are each smaller than a megadungeon and may be completely explored in only a session of so of play. They are presumably part of some adventure storyline which gives the PCs reason to visit them and ties them into the greater milieu or Grand Campaign.

The creators of C&S state their goal of creating a game where the dungeon and wilderness adventure are only part of the game experience. Adventure can also be found in social interaction, feudal tournaments, formal warfare, politics and economics and C&S encourages players to explore these areas as well as in the places of mystery and treasure. I have never gamed C&S as a system, but many of the ideas found in this 1977 publication influence the way I play all other roleplaying and adventure games.

Thursday, December 3, 2015

The Realism Bug-a-Boo

It's a Game!

White box has it's roots deeply set in wargaming, which preceded it by a century or so and had gained a degree of popularity a decade or so before white box with the publication of Avalon Hill strategy games and various rules for wargames using miniature figures. Wargaming combined game mechanics with a desire to simulate the troops, terrain and conditions of various historic military battles using available data. Simulation, of course, implies a connection to reality. Game designers balance a need for fun and playability with a desire to model the most realistic simulation of actual events possible in order to place the players in a sort of "time machine" where they can experience what it was like to be there, in command, on some historic battlefield.

According to gamer legend, Mr. Gygax and Mr. Arneson, the authors of white box, were avid wargamers and one can still find wargame miniatures rules and boardgames written or co-authored by them. At some point they came upon the idea to combine their interest in fantastic literature, sword & sorcery tales, and their love of wargaming. The Blackmoor and Greyhawk campaigns and white box was the result. White box rules contain many abstractions that allow the game to handle various happenings in the "real world" using available data and taking into account a random factor producing an outcome that has important implications for future in game situations and events including success or failure. Abstractions are common in gaming and to some degree unavoidable as we can hardly go around hacking at each other with steel swords, lopping off arms.

The white box introduced lots of people, both wargamers and non-wargamers to a new type of hobby game. I don't know if wargamers and non-wargamers differ regarding their desire for realism in their games, but being a wargamer I recall going through a period where I sought rules with a more transparent connection to what I perceived as the reality of medieval fantasy. In one respect it seems rather silly to talk about realism in connection with gaming in a fantasy/make-believe setting, let alone realistic magic, but such discussions are as old as the hobby.

Mr. Gygax occasionally spoke about the bug-a-boo of realism in fantasy gaming and pointed out the rather non-realistic nature of such an elusive goal as realism in gaming. By contrast, he would also include such mechanics as weapon verses armor class modifiers in Greyhawk and the advanced game player's handbook in an obvious attempt to add realistic detail and complexity. Many game designers and house-ruling referees make similar attempts to bring more realism to their game. At some point they often (re)discover the need for balance between fun and realistic detail.

Abstract game mechanics can provide very realistic outcomes if properly designed. Perceived realism is therefore often a matter of the transparency of details that the gamer can see are effecting the outcome such that "this" and "that" are taken into account. There is no doubt that some members of the hobby will continue to prefer more overt realism and therefore detail and complexity in their game than others will. (Some may even prefer less.) For a game like white box that is easily modified and added to, this becomes just a matter of house-ruling or taking the game beyond the rules as written. For those desiring published rules written with more realism in mind, there are plenty to choose from.

White box has it's roots deeply set in wargaming, which preceded it by a century or so and had gained a degree of popularity a decade or so before white box with the publication of Avalon Hill strategy games and various rules for wargames using miniature figures. Wargaming combined game mechanics with a desire to simulate the troops, terrain and conditions of various historic military battles using available data. Simulation, of course, implies a connection to reality. Game designers balance a need for fun and playability with a desire to model the most realistic simulation of actual events possible in order to place the players in a sort of "time machine" where they can experience what it was like to be there, in command, on some historic battlefield.

According to gamer legend, Mr. Gygax and Mr. Arneson, the authors of white box, were avid wargamers and one can still find wargame miniatures rules and boardgames written or co-authored by them. At some point they came upon the idea to combine their interest in fantastic literature, sword & sorcery tales, and their love of wargaming. The Blackmoor and Greyhawk campaigns and white box was the result. White box rules contain many abstractions that allow the game to handle various happenings in the "real world" using available data and taking into account a random factor producing an outcome that has important implications for future in game situations and events including success or failure. Abstractions are common in gaming and to some degree unavoidable as we can hardly go around hacking at each other with steel swords, lopping off arms.

The white box introduced lots of people, both wargamers and non-wargamers to a new type of hobby game. I don't know if wargamers and non-wargamers differ regarding their desire for realism in their games, but being a wargamer I recall going through a period where I sought rules with a more transparent connection to what I perceived as the reality of medieval fantasy. In one respect it seems rather silly to talk about realism in connection with gaming in a fantasy/make-believe setting, let alone realistic magic, but such discussions are as old as the hobby.

Mr. Gygax occasionally spoke about the bug-a-boo of realism in fantasy gaming and pointed out the rather non-realistic nature of such an elusive goal as realism in gaming. By contrast, he would also include such mechanics as weapon verses armor class modifiers in Greyhawk and the advanced game player's handbook in an obvious attempt to add realistic detail and complexity. Many game designers and house-ruling referees make similar attempts to bring more realism to their game. At some point they often (re)discover the need for balance between fun and realistic detail.

Abstract game mechanics can provide very realistic outcomes if properly designed. Perceived realism is therefore often a matter of the transparency of details that the gamer can see are effecting the outcome such that "this" and "that" are taken into account. There is no doubt that some members of the hobby will continue to prefer more overt realism and therefore detail and complexity in their game than others will. (Some may even prefer less.) For a game like white box that is easily modified and added to, this becomes just a matter of house-ruling or taking the game beyond the rules as written. For those desiring published rules written with more realism in mind, there are plenty to choose from.

Wednesday, December 2, 2015

Chivalry & Sorcery

Reading RPG

I read way more RPGs and game play aid material than I can ever use. Call it a sub-hobby, or whatever. Sometimes I borrow ideas from my reading and it will show up in a game I am running. Sometimes the material just serves as inspiration, inspiration to do better, inspiration to be more creative, inspiration to continue to be excited about this great hobby. Chivalry & Sorcery (C&S) is one of those early (1977) first generation games that attempt to improve on the white box. I have never played C&S, but I have read through it's 6-point type content many times and continue to be inspired by it.

According to gamer legend, Ed Simbalist and Wilf Backhaus were playing white box and wanting more, more medieval feel, more realism, more on what their PCs were doing when not swinging swords and casting spells. So they created answers in the form of their own game. The authors went to GenCon with a variant of the white box in hand hoping to interest TSR in publishing it, maybe as a supplement like Greyhawk, maybe as a stand-alone game like Empire of the Petal Throne. TSR had done both. As the story goes, Mr. Simbalist and Mr. Backhaus changed their minds about offering their game, titled Chevalier, to TSR and instead signed on with Fantasy Games Unlimited. The resulting rewrite became C&S.

C&S seems to take the medieval part of the white box subtitle seriously. The LBBs nominally use the European middle ages as a reference point with regard to castles, royalty, weapons and armor. White box is more heavily influenced by myth and sword & sorcery literature, but the game does derive from Chainmail, a set of miniature rules for medieval era wargaming. C&S is clearly a reaction to white box and its authors make several references to "other games" which do things in a manner inconsistent with either history or logic, such as the "dungeon crawl". The historic feudal period is described in C&S terms of knighthood and social obligation and social class can determine many aspects of the PC. There is an emphasis on the players familiarizing themselves with the medieval "mindset" and attempting to play their characters using such "mindset". Presumably this means with deference for one's social betters and keeping to one's station in life, acting in a chivalrous manner and paying close attention to honor and piety. Default religion in C&S is the medieval catholic church.

The authors state early on that their own campaign is loosely set in France in the year 1170. C&S is not strictly a game about role-playing history, however. The view presented of feudal Europe leaves out the oppression and other unpleasant aspects of the period altogether and portrays a somewhat romanticized and sanitized view of the period. Also, elves, dwarves and hobbits straight out of Tolkien are available as PCs with no real explanation of how to logically insert such anachronisms/fantasies into the historic milieu. With it's magick system and list of creatures, C&S is firmly in the fantasy RPG category of games, but one that seeks to take a much more realistic view of the medieval feudal components.

C&S advertises itself as the most complete game available and I think I understand what they mean by this claim. C&S is often described as three games in one. The grand campaign, as they call it, is somewhat innovative in that the PCs play out their "ordinary" lives interacting with the environment, making alliances and acquiring favors, honor and wealth. They engage in romance, establish families and ties to NPCs. It is this level of play that I assume the author's direct their comments about staying in a medieval "mindset". There is a set of miniatures rules to play out army conflicts on the tabletop using miniature figures grouped into units. And third, there is the adventure or roleplaying game where PCs may engage in treasure hunts, wilderness and dungeon adventures in a manner similar to typical white box play.

C&S offers the hobbyist a somewhat more rounded, complete play experience, provided the players are willing to put forth the extra effort demanded by such a game. C&S requires a bit of homework on the part of the players in order to familiarize themselves with the differences that existed within medieval society and thinking. It requires additional roleplaying effort to "stay in character" when playing the "medieval" PC. In an effort to be more realistic, the mechanics of combat and magick are more complex than in games such as white box. The grand campaign probably requires more playing time than traditional campaigns because one presumably plays out many aspects of the PCs "lives" that are generally glossed over.

In C&S authors Ed Simbalist and Wilf Backhaus have striven to take the roleplaying experience beyond the white box on several levels, completeness, realism and complexity of combat, immersion in the feudal society of a romanticized middle ages and in the process have written a game that I find enjoyable to read containing many cleaver game innovations and much good advice for referees of any fantasy RPG.

I read way more RPGs and game play aid material than I can ever use. Call it a sub-hobby, or whatever. Sometimes I borrow ideas from my reading and it will show up in a game I am running. Sometimes the material just serves as inspiration, inspiration to do better, inspiration to be more creative, inspiration to continue to be excited about this great hobby. Chivalry & Sorcery (C&S) is one of those early (1977) first generation games that attempt to improve on the white box. I have never played C&S, but I have read through it's 6-point type content many times and continue to be inspired by it.

According to gamer legend, Ed Simbalist and Wilf Backhaus were playing white box and wanting more, more medieval feel, more realism, more on what their PCs were doing when not swinging swords and casting spells. So they created answers in the form of their own game. The authors went to GenCon with a variant of the white box in hand hoping to interest TSR in publishing it, maybe as a supplement like Greyhawk, maybe as a stand-alone game like Empire of the Petal Throne. TSR had done both. As the story goes, Mr. Simbalist and Mr. Backhaus changed their minds about offering their game, titled Chevalier, to TSR and instead signed on with Fantasy Games Unlimited. The resulting rewrite became C&S.

C&S seems to take the medieval part of the white box subtitle seriously. The LBBs nominally use the European middle ages as a reference point with regard to castles, royalty, weapons and armor. White box is more heavily influenced by myth and sword & sorcery literature, but the game does derive from Chainmail, a set of miniature rules for medieval era wargaming. C&S is clearly a reaction to white box and its authors make several references to "other games" which do things in a manner inconsistent with either history or logic, such as the "dungeon crawl". The historic feudal period is described in C&S terms of knighthood and social obligation and social class can determine many aspects of the PC. There is an emphasis on the players familiarizing themselves with the medieval "mindset" and attempting to play their characters using such "mindset". Presumably this means with deference for one's social betters and keeping to one's station in life, acting in a chivalrous manner and paying close attention to honor and piety. Default religion in C&S is the medieval catholic church.

The authors state early on that their own campaign is loosely set in France in the year 1170. C&S is not strictly a game about role-playing history, however. The view presented of feudal Europe leaves out the oppression and other unpleasant aspects of the period altogether and portrays a somewhat romanticized and sanitized view of the period. Also, elves, dwarves and hobbits straight out of Tolkien are available as PCs with no real explanation of how to logically insert such anachronisms/fantasies into the historic milieu. With it's magick system and list of creatures, C&S is firmly in the fantasy RPG category of games, but one that seeks to take a much more realistic view of the medieval feudal components.

C&S advertises itself as the most complete game available and I think I understand what they mean by this claim. C&S is often described as three games in one. The grand campaign, as they call it, is somewhat innovative in that the PCs play out their "ordinary" lives interacting with the environment, making alliances and acquiring favors, honor and wealth. They engage in romance, establish families and ties to NPCs. It is this level of play that I assume the author's direct their comments about staying in a medieval "mindset". There is a set of miniatures rules to play out army conflicts on the tabletop using miniature figures grouped into units. And third, there is the adventure or roleplaying game where PCs may engage in treasure hunts, wilderness and dungeon adventures in a manner similar to typical white box play.

C&S offers the hobbyist a somewhat more rounded, complete play experience, provided the players are willing to put forth the extra effort demanded by such a game. C&S requires a bit of homework on the part of the players in order to familiarize themselves with the differences that existed within medieval society and thinking. It requires additional roleplaying effort to "stay in character" when playing the "medieval" PC. In an effort to be more realistic, the mechanics of combat and magick are more complex than in games such as white box. The grand campaign probably requires more playing time than traditional campaigns because one presumably plays out many aspects of the PCs "lives" that are generally glossed over.

In C&S authors Ed Simbalist and Wilf Backhaus have striven to take the roleplaying experience beyond the white box on several levels, completeness, realism and complexity of combat, immersion in the feudal society of a romanticized middle ages and in the process have written a game that I find enjoyable to read containing many cleaver game innovations and much good advice for referees of any fantasy RPG.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)